In today’s rapidly urbanizing world, where technology evolves quickly and environmental consciousness is rising, urban mining has become a game-changing strategy for material recovery and resource sustainability. This innovative approach does not involve digging deep into the Earth’s crust. Instead, it focuses on extracting valuable metals and minerals from discarded electronics, old infrastructure, and other urban residues.

Image Credit: pictures of/Shutterstock.com

Reclaiming these above-ground resources enhances supply chain stability, reduces greenhouse gas emissions, and boosts local employment, effectively turning waste into a strategic reserve. This article explores how urban mining meets the increasing demand for critical resources, eases environmental pressures, and helps shape a circular economy.

What is the Meaning of Urban Mining?

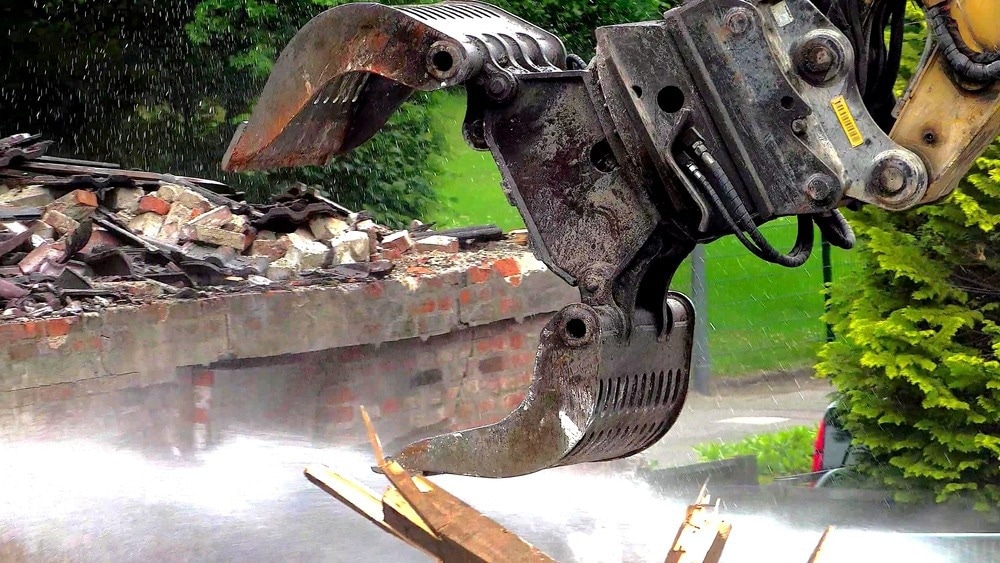

Urban mining targets what is known as "urban ore," which is sourced from old electronics, discarded vehicles, demolished buildings, and even wastewater treatment sludge. Precious metals like gold and platinum frequently appear in circuit boards, copper is typically found in electrical wiring, and elements such as indium or cobalt are present in various electronic components.

Metals from dismantled infrastructure and building materials from construction and demolition debris also comprise a significant portion of recoverable resources. Commonly overlooked items, such as used batteries or broken smartphones, could be treasure troves of raw materials if we collect and process them effectively.1

Why Urban Mining Has Become Increasingly Relevant

The driving force behind the growing interest in urban mining is the global scarcity of many essential commodities. The high demand for metals in electronic devices strains traditional mining operations and is both energy-intensive and costly, often bringing about social and environmental repercussions.

As the world faces the depletion of easily accessible mineral deposits, innovators are looking for alternatives to ensure a steady, cost-effective supply. Urban mining is emerging as a strategic solution, promising a reliable source of materials and a reduced environmental footprint compared to traditional extraction methods.1,2

Moreover, urban mining aligns seamlessly with the evolving circular economy concept. By recovering materials from waste, we can close the loop, ensuring resources remain in circulation rather than ending up in landfills. This approach helps tackle overconsumption, rising landfill costs, and the complexities of managing vast amounts of municipal solid waste. It also reduces reliance on virgin materials, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and minimizing land disturbances from conventional mining.1,2

What is the Urban Mining Approach?

Urban mining involves a combination of collection, sorting, and processing techniques enhanced by innovative technologies. It typically begins with targeted waste collection—think obsolete electronics or construction rubble. These materials then head to specialized facilities equipped with sophisticated machinery.

At these facilities, automated sorting systems powered by artificial intelligence and robotics differentiate materials based on conductivity, density, and magnetic characteristics. Various efficient extraction methods help reclaim valuable metals, minerals, and precious elements like gold or platinum, from mechanical shredding to chemical leaching.2,3

For e-waste, circuit boards are dismantled to extract copper wiring, rare earth magnets, and semiconductor materials. Metals like steel or aluminum are salvaged in construction debris, and concrete and masonry are crushed into aggregates for reuse. Companies at the forefront of these technologies continuously refine their processes to improve yields and reduce environmental impacts.2,3

What are the Benefits of Urban Mining?

Urban mining offers numerous economic benefits. Businesses can cut costs by sourcing metals and materials locally from waste streams rather than buying pricey virgin commodities on the global market. This stable access to valuable resources helps shield manufacturers from price volatility, enhancing supply chain resilience.

New industries centered around recycling, refurbishment, and resource recovery are emerging, creating jobs in technical, engineering, and operational fields. This growth spurs further research and innovation, solidifying urban mining as a dynamic economic force.4

Urban mining is vital for ecosystem protection. Reusing materials already within cities reduces the need for new mining projects that disrupt habitats, produce harmful tailings, and consume vast amounts of energy.

Recycling metals emits fewer greenhouse gases than extracting them from ore, aiding nations in meeting climate goals. As landfill volumes shrink and natural areas remain undisturbed, urban environments benefit from cleaner air, less pollution, and healthier living conditions.4

What are the Limitations of Urban Mining?

While urban mining holds great promise, it is not without challenges. Efficiently collecting and sorting diverse waste streams can be problematic as consumers often dispose of electronics carelessly, and infrastructure for waste retrieval is often lacking. The varying quality of recovered materials due to different product designs complicates extraction processes.

Regulatory frameworks also differ widely, leading to disparities in standards and compliance. Improved policies, consumer education, and enhanced recycling networks can address these challenges.2,3

The Future of Urban Mining

Looking ahead, technological advancements are set to refine material recovery methods, increasing efficiency and extraction rates. Industry standards that promote easier disassembly and material recovery could become more common, facilitating smoother operations.

Global cooperation and shared best practices could streamline regulations, leading to broader adoption of urban mining practices. As cities expand and resource demands grow, urban mining will likely become integral to sustainable development strategies, reinforcing its role in the transition toward closed-loop economies and responsible resource management.3,4

Rethinking Future Resources

Urban mining reimagines built environments and everyday objects as valuable resource reserves instead of mere waste. By methodically recovering metals, minerals, and construction materials from urban settings, we reduce dependence on traditional mining, curb environmental degradation, and promote sustainable economic growth. This practice is not just about technological innovation, it reflects a cultural shift toward prioritizing resource stewardship, ecosystem health, and resilience for the future.

As urban populations increase and consumption patterns evolve, the importance of embracing urban mining only intensifies. Investigating ways to unlock the latent value in discarded electronics, spent batteries, and outdated building materials is becoming crucial. Could urban mining become as routine and essential as municipal recycling programs?

The answer lies in collective action: policymakers creating favorable regulations, businesses investing in recovery technologies, and individuals recognizing the value in every discarded item as a chance to secure a sustainable future.

References and Further Reading

- Tejaswini, M. et al. (2022). Sustainable approach for valorization of solid wastes as a secondary resource through urban mining. Journal of Environmental Management, 319, 115727. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115727. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301479722013007

- Aldebei, F., & Dombi, M. (2021). Mining the Built Environment: Telling the Story of Urban Mining. Buildings, 11(9), 388. DOI:10.3390/buildings11090388. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-5309/11/9/388

- Udage Kankanamge, A. K. et al. (2023). Towards a Taxonomy of E-Waste Urban Mining Technology Design and Adoption: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 16(15), 6389. DOI:10.3390/su16156389. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/16/15/6389

- Kakkos, E. et al. (2020). Towards Urban Mining—Estimating the Potential Environmental Benefits by Applying an Alternative Construction Practice. A Case Study from Switzerland. Sustainability, 12(12), 5041. DOI:10.3390/su12125041. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/12/5041

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.