The concentrator plays a central role in the production of saleable product from mined ore, making it a key target for optimization. It processes the incoming ore into concentrate and waste tailings using unit operations such as grinding and froth flotation.

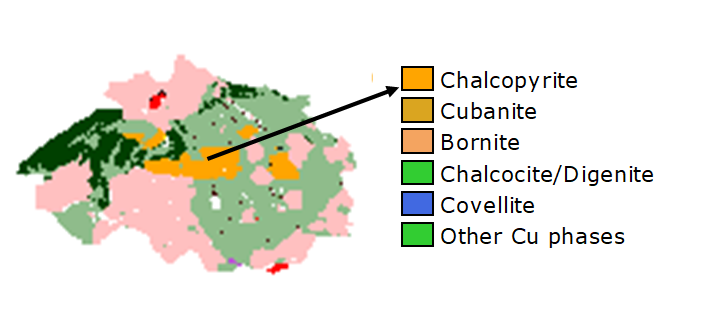

Mineral grades found in concentrator feedstocks can range from less than 1 % to several percent, depending on the characteristics of the ore body.

The concentrator is used to upgrade feed ore into a sellable product via a chemical and mechanical separation process known as froth flotation. Froth flotation enables the selective separation of valuable sulfide minerals from the host rock, separating these into a concentrate and a waste stream known as ‘tailings.’

Concentrates can contain over 20 % of the target mineral by weight, while material that is not recovered as concentrate is transferred to a waste stream before being placed in a permanent storage facility known as a ‘tailings impoundment.’

The tailing stream has low value and can potentially have adverse impacts on health, safety, and the environment. The concentrator should ideally convert as much of the valuable mineral to a sellable concentrate as possible, achieving this at the lowest practical cost while minimizing any losses of the mineral to tailings.

‘Recovery’ in this context refers to the percentage of valuable mineral or metal in the feed stream that reports to the concentrate. This is a widely utilized performance benchmark.

On-line elemental analysis is commonly employed by mineral processors in order to improve concentrator recovery and reduce OPEX. These real-time assays of multiple process streams represent a robust foundation for process control, allowing operators to observe and react in real time to trends in process changes that could potentially affect recovery.

Assays provided by on-line analyzers support a range of uses, for example, the addition of collector reagent based on the real-time analysis of metal content in the feed, the improvement of concentrate value, and, more generally, the establishment of a highly efficient, knowledge-led approach to optimized concentrator operation.

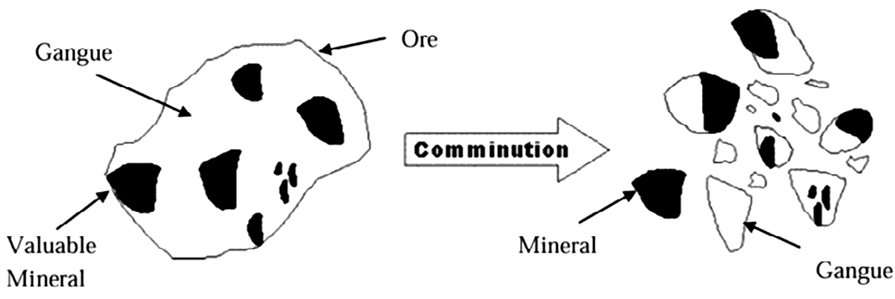

Figure 1. Valuable mineral grains are heterogeneously distributed in blasted, crushed mineral ore making comminution essential to their release. Image Credit: Thermo Fisher Scientific

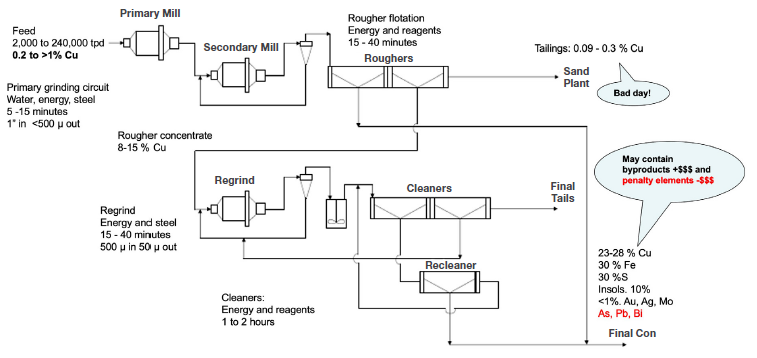

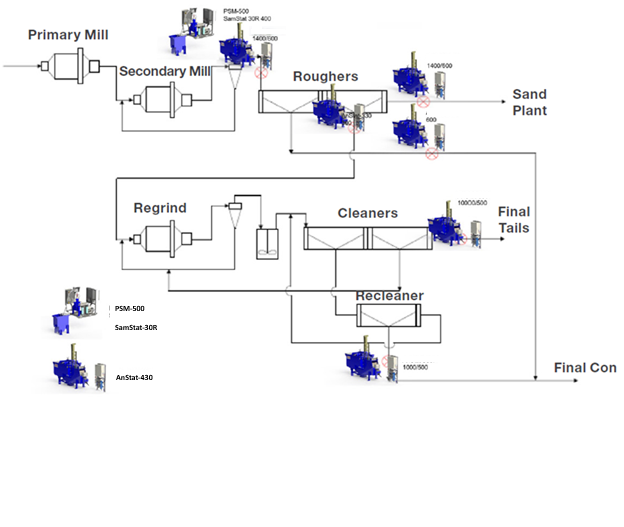

Figure 2. Schematic for a copper concentrator showing rougher and cleaner circuits. Image Credit: Thermo Fisher Scientific

The Challenge of Concentration

Mineral grains of interest tend to be present in the size range 10 to 100 µm. These minerals will be heterogeneously distributed in the blasted, crushed rock that makes up the feed to the concentrator (Figure 1).

Liberating these grains requires comminution, grinding the rock to progressively finer particle sizes, and separation of waste particles from those particles containing valuable mineral content.

It is rarely possible to achieve mineral liberation in a single stage of size reduction. Rather, this is most commonly done via multiple steps of comminution and froth flotation separation, for example, in a copper concentrator (Figure 2).

In the example presented here, particle size would be progressively reduced from below 30 mm in the feed, reaching less than 500 µm in the primary grinding circuit before being further reduced to ~50 µm in the regrind and cleaner circuit.

Grinding to a finer particle size will improve the chance of liberating a mineral grain from the host rock. Once this has been separated from the host rock, it can then be selectively upgraded to a concentrate.

It is also important to note that not all mineral grains will be fully liberated by grinding to a finer particle size, and several particles containing smaller mineral grains will continue to remain locked with host rock minerals. It is not economically viable or even possible to achieve 100 % recovery, processing ores to the point of them being entirely valuable minerals or entirely waste.

Grinding to a finer particle size will reduce milling circuit throughput while simultaneously increasing grinding media costs and power. There is a risk of froth flotation efficiency being compromised by fines, and a risk of value-bearing mineral grains held in certain types of host rock failing to be effectively separated.

Pushing the flotation circuit to recover too high a quantity of value-bearing mineral(s) can also pull over undesirable minerals, increasing impurity levels. For instance, the presence of contaminants like lead, arsenic, and bismuth in a copper concentrate compromises its value to the smelter, reducing the concentrator’s net smelter returns due to the presence of these penalty elements.

Real-time online analysis allows operators to study, experiment with, manage, and optimize each individual process step in order to address these issues, maximize profitability, and confidently balance grade and recovery.

Online Sampling and Analysis Considerations

Using centralized and dedicated analyzers is an efficient way to monitor the concentration process. Centralized analyzers are capable of measuring multiple process streams in sequence, making them useful for broader system oversight. Dedicated analyzers, on the other hand, are each assigned to a single stream and provide continuous monitoring, which is especially important when real-time data is needed for process control.

Key considerations include:

- Process dynamics, including an understanding of how quickly the process changes and any implications of the necessary measurement frequency.

- Measurement cycle time, including the length of time required for a complete measurement.

- If a centralized analyzer is used, the cycle time is required to sequentially measure all the streams going through the analyzer.

- Sample transport, including whether a dedicated or centralized analyzer can be gravity fed to avoid relying on pumps, and whether long sample pipe lengths can be avoided to reduce the risk of blockages.

An investment in dedicated analyzers increases Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) but allows optimal positioning for a specific sampling requirement. This reduces pumping requirements and blockage risks, two factors that attract Operating Expenditure (OPEX) in the form of manual input and energy costs.

This investment also helps deliver effective process control by maximizing measurement frequency and availability.

Rigorous economic assessment is key to deciding which streams should have dedicated sampling and analysis capabilities. This assessment should also consider engineering and construction costs, implementation timelines, and OPEX over the life of the installation. It should also consider opportunities to reduce CAPEX using a centralized analyzer.

Robust system design, such as avoiding the use of sample transport pumps, helps to ensure very high analyzer availability over 95%, which is a requirement when using online assays for concentrator control. Clear process control strategy is needed to make the most of the assays provided by an online analyzer. For operator-based manual control, training is important. High availability of online data is crucial for automated control.

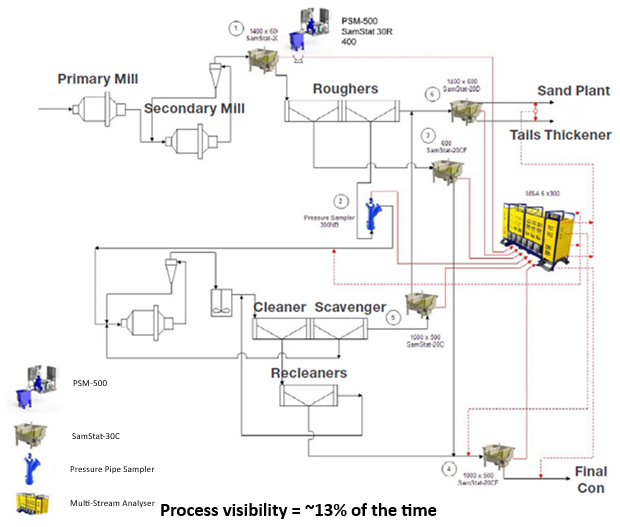

Figure 3. A low CAPEX sampling and analysis solution with a shared elemental analyzer. Image Credit: Thermo Fisher Scientific

Comparing the Performance of Alternative Sampling and Analysis Strategies

Figure 3 shows the sampling setup for the copper concentrator discussed throughout the article.

This setup features two analyzers: one designed to enable particle size control of the primary grinding circuit feeding the first stage of flotation (referred to as the rougher circuit) and another analyzer for elemental analysis.

The elemental analyzer measures a total of six streams from across the concentrator, with each stream taking one minute to analyze. The total measurement cycle time is 8 minutes; however, this means that every 8 minutes, the operator receives one minute of assay per stream. This results in overall process visibility of just ~13 %.

SamStat samplers are selected to minimize head losses and maximize accuracy. Samples can gravity flow to the centralized analyzer, eliminating the need to employ sample transport pumps.

The location of the centralized analyzer is specifically chosen to allow gravity flow of the sample return back to the circuit. A sample return pump may be required in some cases to allow higher value streams to return to the circuit from which they were taken.

This setup enhanced manual process control, delivering a profit increase of $316,000 per month for a customer operating a 50,000 ton per day copper concentrator.

Figure 4. A high measurement frequency sampling and analysis solution with dedicated elemental analyzers. Image Credit: Thermo Fisher Scientific

Figure 4 features an alternative, best-case sampling and analyzer setup, with each stream featuring dedicated elemental analysis capabilities. This solution requires additional CAPEX of $1M (relative to that of the preceding solution), while OPEX is reduced because there are no sample pumps or transport lines to maintain. This approach offers 100 % process visibility.

It is possible to implement process control strategies without complex logic, taking into account measurement delays and cycle times of the centralized approach (Figure 3).

Using published literature linking measurement frequency with Net Smelter Returns (NSR), it is possible to estimate that this system would deliver an additional 2.6 % increase in NSR, leading to an estimated payback time of just a few months for the $1M CAPEX.1 Profitability would continue to be higher for the lifetime of the concentrator once this CAPEX has been repaid.

Conclusion

The combination of online sampling and analysis represents a robust platform for automated concentrator control. This approach offers considerable economic benefit via reduced operating costs and more consistent and improved concentrate quality.

Careful consideration of deliverable value and the steps necessary to achieve this requires the development of a successful implementation strategy for online sampling and analysis.

Equipment choice is essential, particularly the choice between centralized or dedicated analyzers. It is also important to consider operational practice, maintenance, availability, data use, training, process control strategy, and automation, when looking to ensure truly optimal concentrator control.

Acknowledgments

Produced from materials originally authored by Thermo Scientific.

References

- Remes, A., Saloheimo, K. and Jämsä-Jounela, S.-L. (2007). Effect of speed and accuracy of on-line elemental analysis on flotation control performance. Minerals Engineering, 20(11), pp.1055–1066. DOI: 10.1016/j.mineng.2007.01.016. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0892687507000404.

This information has been sourced, reviewed, and adapted from materials provided by Thermo Fisher Scientific – Production Process & Analytics.

For more information on this source, please visit Thermo Fisher Scientific – Production Process & Analytics.