Lithium could be selectively extracted from "low quality" brines using a surprising mechanism discovered at the University of Michigan. The technology could help make brine lakes rich in magnesium a more sustainable source of lithium for batteries and renewable energy technology.

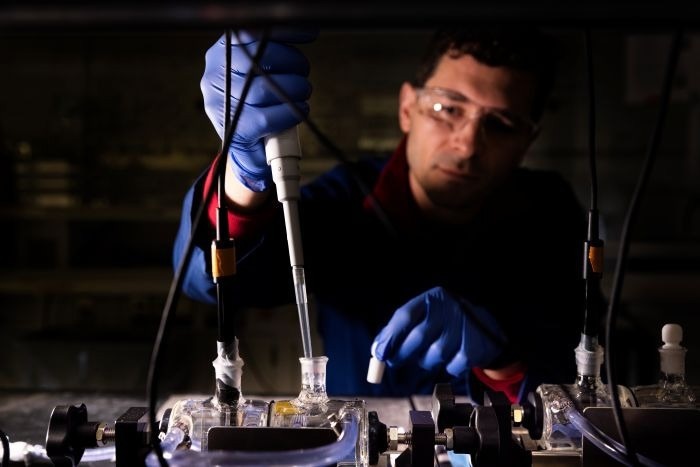

Jovan Kamcev, an associate professor of chemical engineering, takes a brine sample from a diffusion cell. A similar system was used to discover the new lithium extraction method. Image Credit: Marcin Szczepanski, Michigan Engineering

Jovan Kamcev, an associate professor of chemical engineering, takes a brine sample from a diffusion cell. A similar system was used to discover the new lithium extraction method. Image Credit: Marcin Szczepanski, Michigan Engineering

Lithium is currently mined from ore and extracted from brines, or very salty waters. Ore is available in limited quantities, and mines are expensive and hard on the environment, sometimes contaminating drinking water sources with harmful metals and chemicals. Lithium-rich brines, which often exist in nature as salty lakes or groundwater below dry lakes, are a promising alternative – they hold over half of the world's available lithium.

To extract lithium from brines, workers pump the brine into shallow ponds, where it evaporates in the sun. Salt crystals and an even saltier brine are left behind, and chemicals are added to the concentrated brine to pull out the remaining salt.

Magnesium – an element chemically similar to lithium – complicates this conventional process because it forms solids with lithium in the evaporation ponds. In brines where magnesium levels are at least six times higher than lithium, extra chemicals are needed to selectively remove the magnesium, increasing costs and waste.

Because of high magnesium content or low lithium concentrations, the majority of brines are considered low quality for lithium mining. Most of the lithium mined today comes from ore and high-quality brines beneath salt flats in South America.

"In some natural brines, the conventional approach isn't economical, so people aren't utilizing the resource," said Jovan Kamcev, an associate professor of chemical engineering and the corresponding author of the study published in Nature Chemical Engineering. To help find solutions, the U.S. Department of Energy funded the research.

Without economical and sustainable sources of lithium, decarbonization efforts could be jeopardized. Demand could outpace the current lithium pipeline by 2029, according to S&P Global. Tapping into low-quality brines rich in lithium – such as the Smackover Formation brines in Arkansas – could help alleviate the strain.

In the researchers' new method, a negatively charged membrane separates a brine from pure water. Lithium diffuses through the membrane into the pure water, leaving magnesium behind without any external electricity or added pressure. This simple method also works at high salinities, unlike other approaches for separating lithium while it's dissolved, and it uses less water than evaporation ponds, which has been a pain point for communities living near lithium brines.

"This separation strategy can recover lithium without the water-intensive steps that pose sustainability concerns in current technologies," said Lisby Santiago-Pagán, a doctoral student in macromolecular science and engineering and a co-first author of the study.

Normally engineers use electric currents in a process called electrodialysis to separate dissolved elements. In this approach, elements like lithium and magnesium, which exist in water as positively charged ions, are separated from oppositely charged ions as they travel toward a negative electrode, crossing negatively charged membranes on the way. Typically, ions with a stronger positive charge, such as magnesium, would be more attracted to the negative charges and cross first. But when the researchers removed the electric current, and put pure water on one side of the membrane instead of an electrolyte, lithium – the ion with the weaker charge – crossed first.

"This discovery was kind of an accident in the lab, made with control experiments designed for membranes that we were making for electrodialysis," said Kamcev. "We really didn't understand it at first, but we repeated it many times in different testing conditions."

The unexpected behavior is explained by charge balance. For each positive ion that crosses the membrane, a negative ion must also pass through – chloride in the researcher's case. Lithium prefers to balance the charge from the chloride, so when chloride diffuses into the pure water, lithium follows.

The membrane's negative charge also has to be balanced by positive ions, a role preferred by magnesium, as the ion with higher charge. The preference is so strong that any magnesium ions that leak through are quickly sucked up by the negative charges on the membrane. But when an electric current is applied, the magnesium ions gain enough energy to cross the membrane and contaminate the solution.

The new method can't separate lithium from other ions with the same charge, such as sodium, but they could be separated by pairing the new technique with evaporation, lithium-selective adsorbents or chemicals that selectively precipitate lithium.

"The next step is for researchers to do a process and techno-economic analysis to see what processes can actually work together," said Harsh Patel, a doctoral student in chemical engineering and co-first author of the study.

The researchers have applied for patent protection with the assistance of Innovation Partnerships and are seeking partners to bring the technology to market.